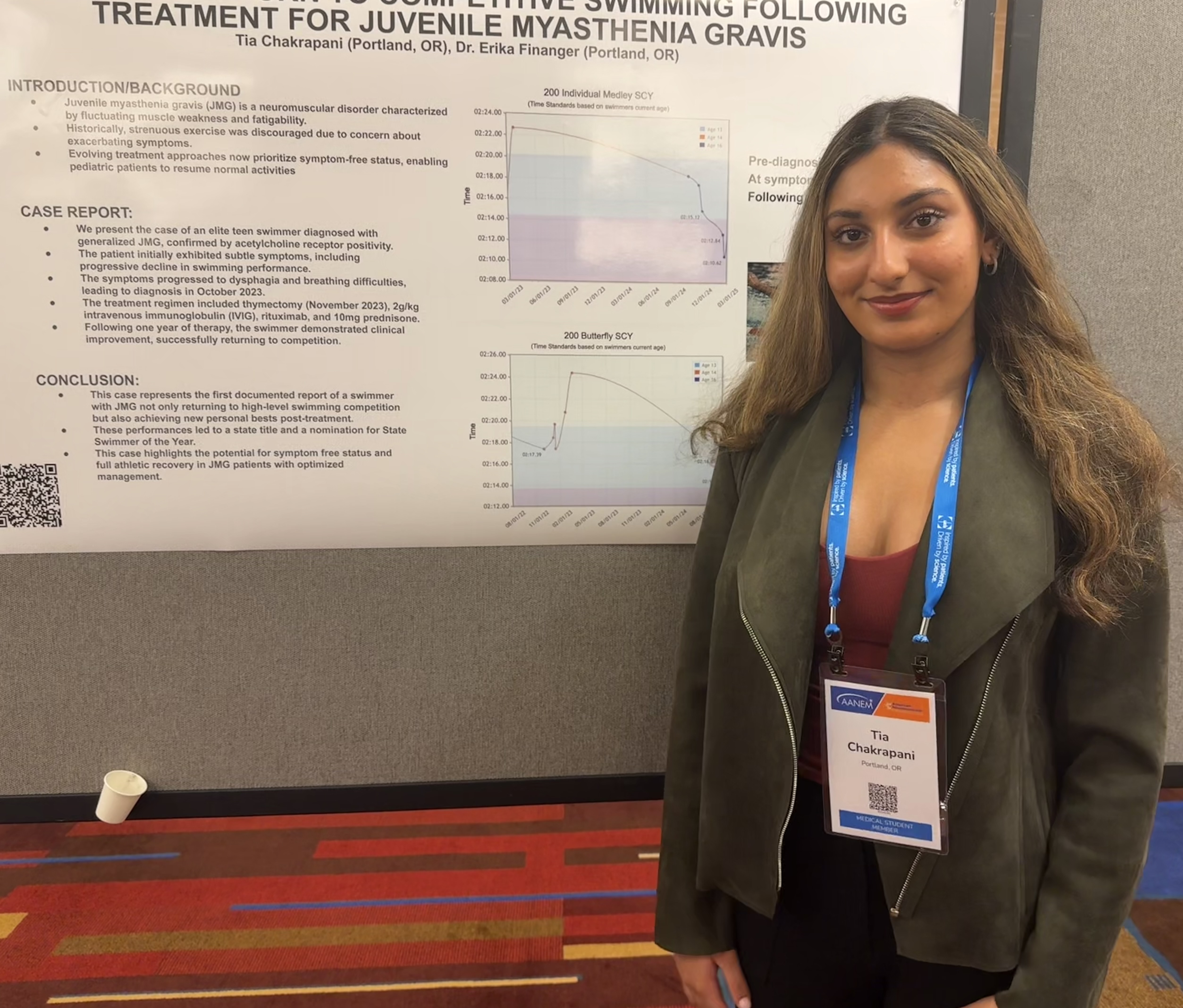

Meet Tia: A competitive swimmer who refused to let misdiagnosis define her

At 14, Tia Chakrapani was living the life she'd built since age seven. As one of the top milers on the West Coast, she was on the national squad, practicing 20 hours a week, and being recruited by D1 college programs. Swimming wasn't just a sport for Tia. It was who she was. The water gave her peace, clarity, and purpose.

Then in January 2023, during championship season, something shifted. After races, Tia couldn't catch her breath. Her oxygen levels dropped into the high 80s on her Apple Watch. The fatigue felt different. Wrong.

"I just didn't feel like myself," Tia remembers. "I didn't feel normal."

But it was flu and COVID season. Everyone thought she was fighting off a virus or maybe just a little out of shape. So Tia did what athletes do. She powered through, thinking this was just a hump she needed to train past.

What followed was eight months of being dismissed, doubted, and disbelieved. Doctor after doctor diagnosed her with asthma, anxiety, or vocal cord dysfunction. Anything but what was actually happening.

One ENT scoped her throat and told her to stop watching the Kardashians because he thought she was mimicking their vocal fry. "I've never watched the Kardashians in my life," Tia says. Her pediatrician told her to stop hyperventilating. She was called hysterical, told she was too Type A, accused of making things up because her swimming times were not dropping.

The worst part? Tia started to believe them.

"After a couple months, I started to believe them," she admits. "You have so many doctors telling you this is what's happening, and I didn't even know what was happening. So it's like, why would I listen to myself over all these people who've been doctors for 30 years?"

She'd lie to her coaches about knee pain or shoulder injuries because she couldn't explain what was really wrong. "I just couldn't move. But that's hard to explain to a coach."

By June, during a meet at Mount Hood, Tia swam the 100 butterfly and couldn't get out of the pool. Her arms wouldn't work. A friend had to pull her out. One of the top distance swimmers on the West Coast couldn't swim across a pool.

When Tia took time off in August and traveled with her family, symptoms seemed to disappear. Looking back at vacation photos now, her mom Andrea can see the ptosis in every picture. But at the time, they didn't know what to look for.

September brought Tia back to the pool and back to reality. She was worse than ever.

Then in early October, Andrea picked Tia up from practice and her face was completely paralyzed. She snapped a photo and sent it to her husband, Tia's father, who's a neuroradiologist. He immediately called a neurologist friend.

"She has myasthenia," the friend said. "We're admitting her tomorrow."

Finally, a diagnosis. AChR+ generalized myasthenia gravis.

"I can't lie, it felt great," Tia says about getting the diagnosis. "I was really happy because for so long we were going to doctors and they all diagnosed me with anxiety, with vocal cord dysfunction, with asthma. Having a name for it was such a relief."

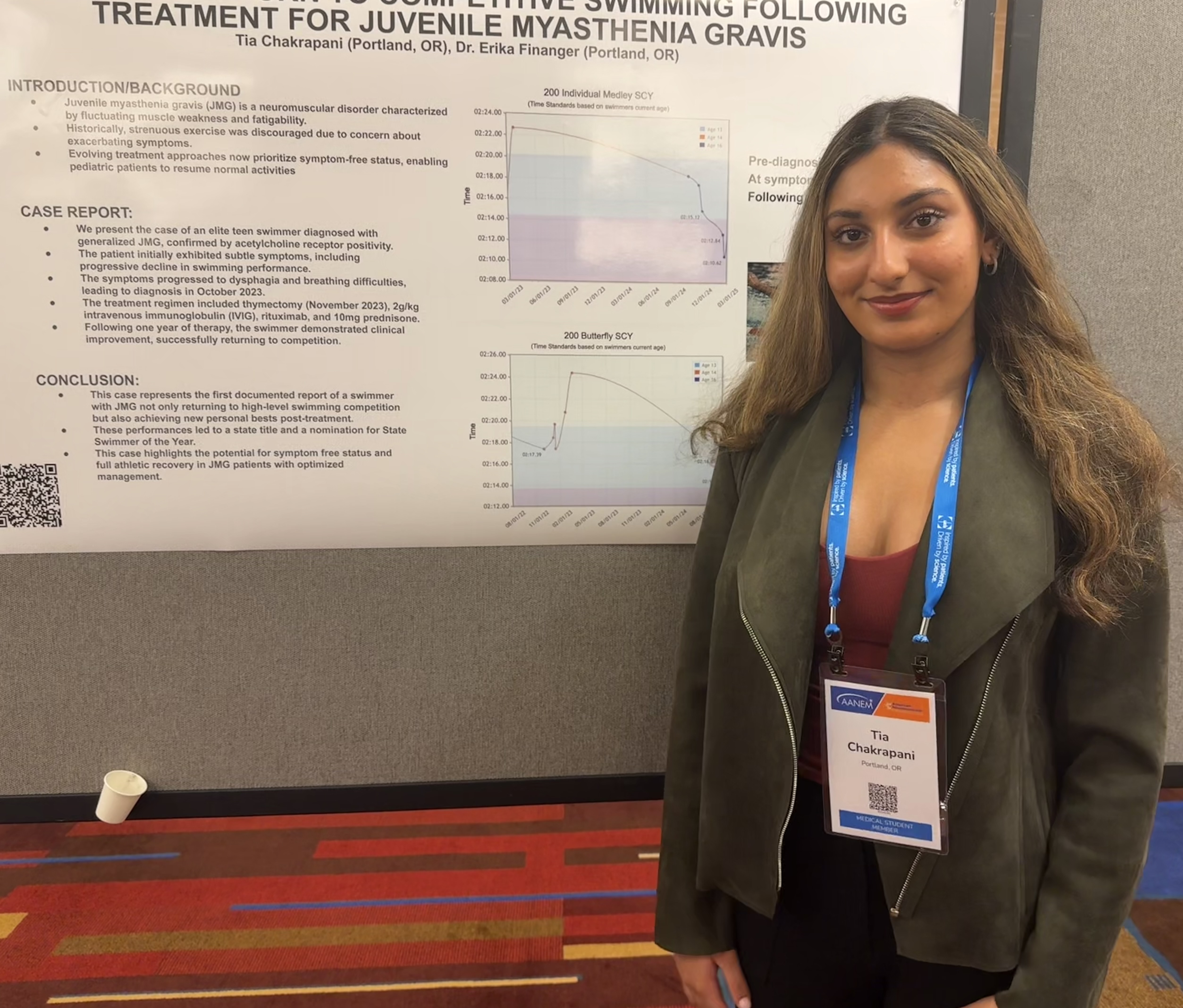

Tia was admitted to OHSU and started on Mestinon."After just the first pill, I felt so much better," she remembers. A month later, she underwent a thymectomy with her parents' former medical school professor. The surgery was supposed to take 90 minutes. It took six hours. Her thymus was so hyperplastic it had wrapped around her phrenic nerve.

Four weeks later, Tia was back in the pool. Her spine was so affected by the transcervical approach that she was "a hunchback for probably a month or two," she says. Swimming helped straighten her out.

But recovery wasn't a straight line. The IVIG gave her splitting headaches for five days after each infusion. "I had to sit in a dark room. It was hell," she says. She eventually switched to weekly SCIG infusions at home so she wouldn't miss so much school.

Then came rituximab and the brain fog. During one practice, her coach explained a set they'd done dozens of times. Tia stood there, completely confused. "I didn't understand it," she says. "Now looking back, it was right after I had a dose of rituximab."

Her parents watched their intellectually sharp daughter struggle with basic comprehension. "It was really upsetting," Andrea says. "You're trying to help your kid with drugs, but something she's extremely good at—being super smart—you're making it decline."

There were other losses too. Tia stopped taking photos because for so long, she couldn't smile. At her swim team's banquet in July 2023, every photo shows a girl who physically couldn't move her facial muscles. Even now, she avoids photos, something that affects her teenage friendships in ways people don't always understand.

"My friends love taking photos when we go out to dinner, prom photos, all that stuff," she says. "That's something I just don't like and I have trouble doing now."

She can't stay out late because fatigue triggers symptoms. She follows a low inflammatory diet, so spontaneous crumble cookie runs with friends aren't an option. While her classmates are sneaking into parties, Tia's on the La-Z-Boy getting her weekly infusion. "I just have to be more conscious about what I do because it does have a bigger effect on me than it would on somebody else."

Today, Tia is doing well. She's on Zilucoplan daily injections, Mestinon as needed, SCIG, and rituximab. She misses school maybe once every six months for myasthenia, though she gets sick more often because she's immunocompromised.

She's also running a nonprofit organization where she talks to other kids with myasthenia and their parents, offering the education and support she desperately needed. Most of the kids she talks to are drastically undertreated, stuck on just steroids when so many options exist.

"I have survivor's guilt," she admits. "I got a thymectomy within a month of diagnosis, which is unheard of. I get the best care, best drugs. That's the reality for basically no one else with myasthenia. So I feel like I'm giving back some of my fortune."

Her first encounter with another person with MG happened during her very first IVIG infusion. Her nurse had been diagnosed with myasthenia at 18. It took her five years to get diagnosed. She nearly died choking on a bagel.

"That could have been a reality for me," Tia says quietly.

Now she's the person on the other end of those Zoom calls, telling families about treatment options their doctors haven't mentioned, explaining what drugs they can advocate for, giving them the knowledge most people don't have access to.

When asked what she wants people to take away from her story, Tia doesn't hesitate.

"The hardest part of getting diagnosed with myasthenia wasn't the drugs, the time spent in the hospital, or the surgery. It was not being believed. I've always been someone very sure of themselves, very confident. Spending all this time going to doctors who said I was anxious or exaggerating—that was 100% the hardest part."

Her advice to doctors? "Always listen to your patient. Maybe nine times out of ten it's asthma, maybe it's anxiety. But there's always that one time, and you don't want to miss a diagnosis like this. It could have detrimental consequences."

And to teenagers newly diagnosed? "Progress is a long road. You're going to get better, then worse, then better again. I'm not the most patient person, so it was really difficult for me. But you've got to take it easy on yourself and go with the flow."

Tia still swims. She still loves hiking and backpacking in the Pacific Northwest. She's thinking about medical school now, not despite her negative experiences with doctors, but because of them.

"I kind of took it as 'I don't want to be a part of this' instead of 'I want to be a part of this so I can make a change,'"she explains. "That's kind of where I'm at now. If I don't do this, who will?"

Through her advocacy work and her own journey, Tia continues to raise awareness about myasthenia gravis and the importance of believing patients. You can learn more about her story and her nonprofit work at tiachakrapani.com.

.png)